I got this feedback from my professor this morning:

“You might need to look into the maturity of your (tribal fusion) art form.”

I literally wandered for a while — what does “maturity” mean in art, and why should an art form be mature? Shouldn’t art be the most innovative thing in the world? Shouldn’t it exist outside of rules?

So I asked GPT. And it said something like this:

“‘Maturity’ in an art form means it has enough depth, structure, vocabulary, and cultural context to express complex ideas and emotions with clarity and originality. It’s not about age — it’s about how fully the form has evolved in terms of technique, theory, audience understanding, and internal diversity.”

Okay. That sounds… logical. A bit dry, but fine. It went on to explain that a mature art form tends to have:

1. Technical Mastery

Artists have refined skill and a shared understanding of form and technique.

2. Cultural and Theoretical Depth

It carries a rich history, multiple schools of thought, and the capacity to address deep human themes.

3. Internal Diversity

It evolves into distinct styles or philosophies, supporting both mainstream and experimental work.

4. Audience Literacy

The audience “gets it.” They can engage, critique, and emotionally connect.

5. Capacity for Innovation

It doesn’t just preserve tradition — it breaks and remakes it, consciously.

It all made sense on paper. But still, why does art need to be mature?

GPT gave some reasons:

So it can express more than surface-level beauty.

So it’s taken seriously (i.e., not dismissed as a fad).

So artists can challenge norms meaningfully, with a context to push against.

So it can support long-term careers and institutions.

Alright. I counted how many boxes tribal fusion checks off, and honestly? At least 80%. It’s an incredibly technical, well-evolved dance form with deep folk roots, serious evolution, and a global community of brilliant dancers. I felt confident asking again:

“Is tribal fusion a mature art form then?”

Surprisingly, GPT still said no. So I looked deeper and found the missing points:

1. Institutional Infrastructure

No formal accreditation. No standard pedagogy. Almost never included in university programs or national art institutions.

2. Public Misunderstanding

Still seen as “just belly dance” or something alternative. Often misunderstood. Plus, it’s tangled in cultural appropriation debates, largely due to its hybrid, cross-cultural nature.

In short: researchers aren’t studying it, and the public doesn’t understand it. Likely because the community, while rich, is still relatively small.

By contrast, hip-hop is now considered mature. Why? Because institutions like Harvard have taken it seriously.

That really hit me — is that all it takes?

It made me sad. Because “maturity” here seems defined by the approval of systems — the academic world, the funding bodies, the mainstream. And honestly? We know what “the public” is like. If you’ve taken even one psych class, you know this: consensus is often the lowest common denominator of taste. The crowd is usually the last to catch up.

So why should art have to follow that?

The purpose of art is to disrupt. To speak what can’t be said, to imagine what hasn’t been imagined. To look backward with defiant depth, or to leap ahead where language fails. That kind of expression — by definition — won’t fit into maturity. Not the way it’s currently defined.

Tribal fusion is not alone in this.

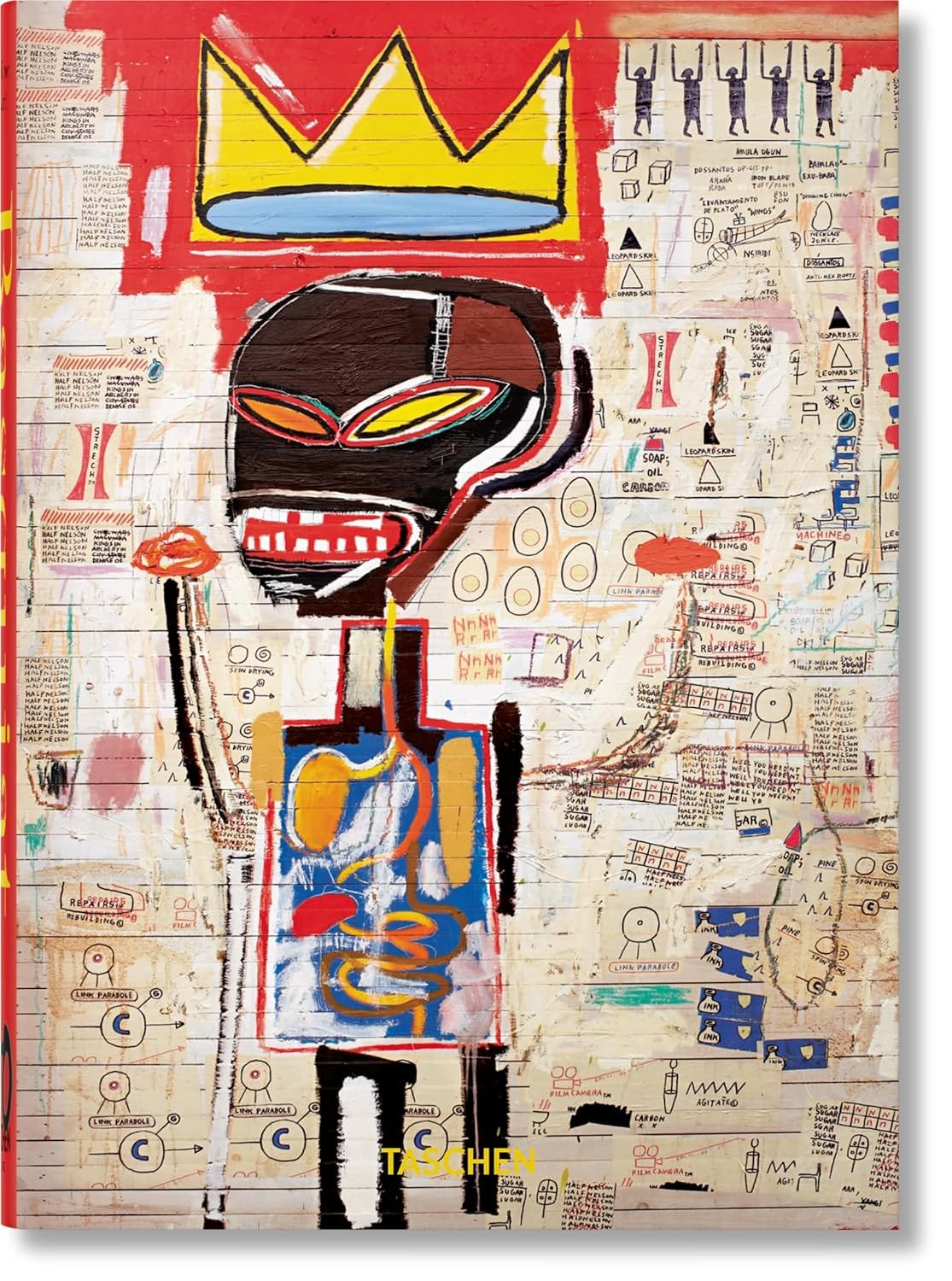

Jean-Michel Basquiat started out spraying cryptic poetry on walls in downtown Manhattan. No training. No degree. Just rage and brilliance and fire. People didn’t call it mature — they called it vandalism. Now his work tore open race, power, beauty, death. Museums caught up later.

Kurt Cobain didn’t sing maturely, either. He didn’t play pretty. Nirvana came from a garage and broke every commercial mold. The music was raw, too loud and too emotional. It didn’t ask to be understood. It just was. Then millions heard their own chaos in it.

Even Frida Kahlo — her art was called strange, grotesque, and most coincidentally, naive. She painted her pain, her disability, her bloodline. That kind of truth doesn’t fit the classic rules of composition. And for decades, she was ignored. It took time and a shift in values for the world to admit her genius.

These people didn’t wait for their art to “mature.” They made it urgent. Alive. Undeniable.

Social norms are slow to change. They always are. So here’s what I’ve decided:

I’ll do what I have to for the system. I’ll present tribal fusion as mature when I need to — when I write academically, when I submit to institutions. I’ll use their language, their frameworks, their boxes.

But in my dancing, I will never make this art form “mature.”

We tribal fusion dancers move in the wild. We listen to the wind and the roots. We learn from the body and the land. Generation by generation, this dance has grown — without permission, without titles, without needing validation.

And it will stay like that.

So do many of the most powerful human art forms.